The ABO Blood Group System is the foundation of everything we do in Transfusion Medicine. If you are wondering how we test patients and donors to determine their ABO type, this quick blog post is for you.

This post also serves as an introduction to episode 054 of the Blood Bank Guy Essentials Podcast. In that episode, Dr. Nicole Draper takes us on a tour of the essentials of recognizing and dealing with ABO discrepancies.

NOTE: In 2011, I published a video covering the basics of the blood groups, including ABO (you can find it on the BBGuy video page). If you want lots more detail on ABO than I can cover here, just watch that video from the 15:30 mark to 33:05. This post will focus on the essentials of ABO testing so you can be better prepared for the cases Nicole will discuss in the podcast.

Overview:

The ABO Blood Group System is clearly the most important system, since just about everything we do in blood banking revolves around ensuring that a donor and a recipient are either “ABO-compatible” (the definition varies somewhat by product, but in general, that means the recipient does not have an ABO antibody that would harm the transfused donor red blood cells) or “ABO-identical” (donor and recipient have exactly the same ABO type).

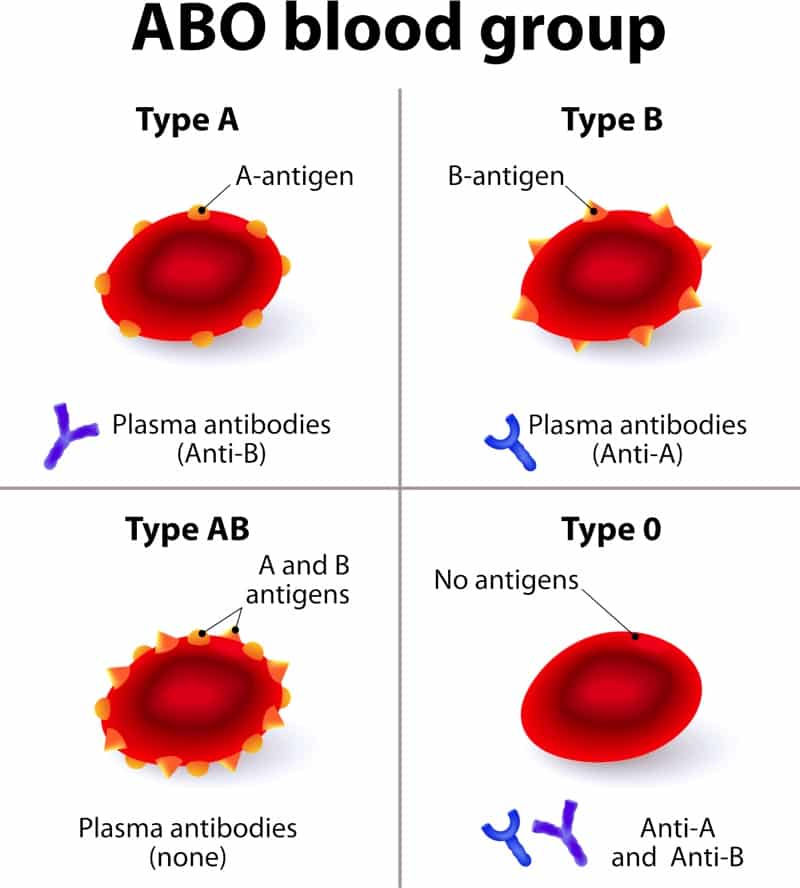

In order to better understand our tests, you have to know a little bit about the antigens and antibodies that define someone’s ABO type.

Antigens and Testing:

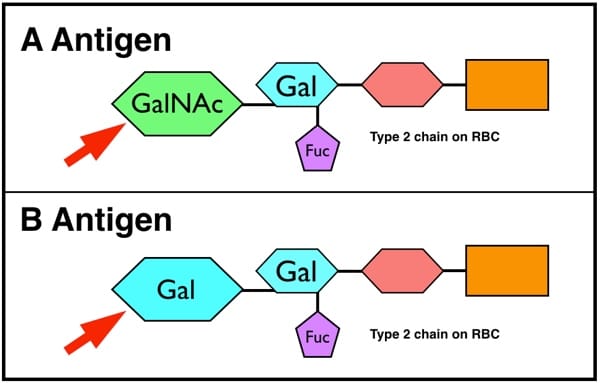

There are only two antigens you have to know in the ABO system (don’t let the name fool you!); they are cleverly known as “A” and “B.” Amazingly enough, given how important it is to distinguish between the blood groups, these two antigens differ by exactly ONE sugar residue added by one of two different enzymes. You can learn more details about ABO biochemistry in the video I mentioned above, but I’ve placed an image that shows you the difference below.

GalNAc=N-acetylgalactosamine

Gal=Galactose

A person with the A transferase enzyme will make A antigen on their red blood cells (RBCs), while someone with the B transferase makes B. The small number of people who have both enzymes will make both antigens, and those who lack both enzymes will make neither. Simple, right?

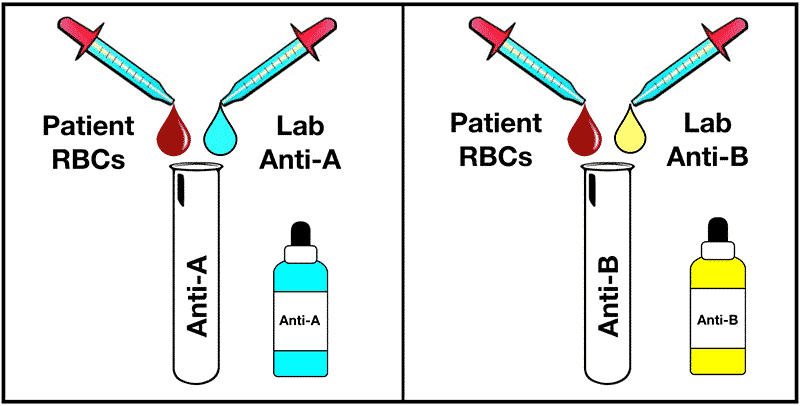

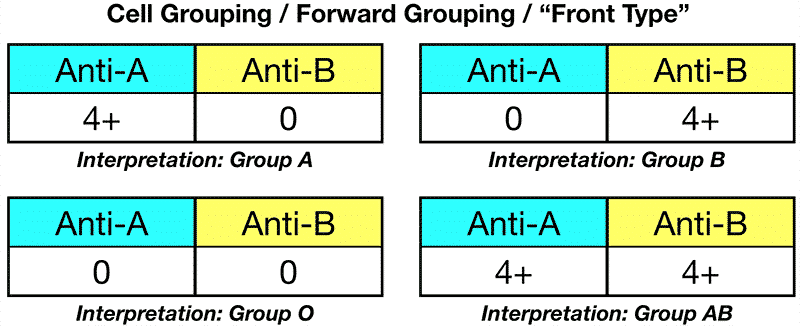

The first part of laboratory testing to determine someone’s ABO type just answers the question, “Does this person have A, B, both, or neither on their red cells?” This test is really straightforward, and few have trouble understanding it. We just separate the plasma and red cells from the person to be tested (by spinning the sample tube really fast), and then we mix the person’s red cells with really strong, laboratory-derived antibodies against the A antigen (“anti-A”) and the B antigen (“anti-B”). Hey, don’t let anyone confuse you: There is no such thing as an “O” antigen, and neither do we use “anti-O” in our testing. Here’s how it looks:

This test goes by several names, depending on whom you ask! Most blood bankers call it the “front-type,” but others call it “cell grouping” or “forward grouping.” Whatever you call it, this simple test gets you halfway to determining someone’s ABO type.

Also, those preparing for standardized exams should note that, by convention in most of the world, the reagent (laboratory) anti-A is colored blue, while anti-B is colored yellow. Why? Practically, it is so the blood bank worker can glance at the tube and see whether or not the antibody was actually added. Sadly, anti-B is not blue, because that would be really easy to remember, wouldn’t it? The outrage!!

Again, the pattern of how the person’s cells react with those two antibodies determines the interpretation of the ABO group on the cell grouping test. There are really only four patterns that are seen in the VAST majority of people being typed. Those four are shown below.

Tips and Tricks for Cell Grouping Interpretation:

- The reactions are almost always very strong. The anti-A and anti-B we use are monoclonal and extremely potent! They have no trouble directly and strongly agglutinating red cells of the appropriate type, so if you see a reaction that’s anything other than a 3+ or 4+ (very strong, in other words), something is not right!

- ABO testing was traditionally done in test tubes or on slides (as I show it above), but today, it’s very commonly done using either one of the newer methods, commonly called “gel” and “solid phase.” Both of those platforms can be automated, to make things easier for blood bank workers. To learn more about those platforms, you can watch my pretransfusion testing video from 21:50 to 27:40

- Subgroups happen. I mentioned earlier that A and B antigens are formed by activity of enzymes that help add a single sugar residue. Well, some people (primarily those of blood group A) may inherit less effective forms of those enzymes from their parents, and when they do, it’s possible the A antigen may be present in a weaker form than normal. We call this having an “A subgroup,” and there are many of them (but that gets beyond where I’m trying to go with this post). Note that there are B subgroups, too, but they are uncommon and we usually don’t see them).

- Sometimes, things go wrong. In some cases, antigens will be absent when they should be present. In others, we may see an “extra” antigen. In both of those scenarios (which Dr. Draper outlines nicely in the podcast), it’s important to evaluate your forward (cell) grouping with the reverse (serum) grouping.

Antibodies and Testing:

When humans are born, we have no ABO antibodies of our own (we may have a few floating around from our mom, but we haven’t made any yet). As we start to live, within the first few months we are exposed to a multitude of bacteria both in the environment and in our digestive system. Some of those bacteria contain antigens that look “just like” human A and B antigens. As a result, by the time babies get to 3-6 months of age, they generally start making their own ABO antibodies (NOTE: Blood bankers call these antibodies a fancy name: “Isohemagglutinins”).

Which antibodies, you ask? Well, there are at least two, and they should make total sense to you. The first is anti-A, and it would be made only by people who see the A antigen in the environment, recognize it as “foreign” (in other words, “hey, I don’t have that protein in my body!”), and form an antibody against it. So, think about it: If you are group B or group O, you do not have the A antigen on your cells, so you are eligible to make anti-A. In the same way, people form the second antibody, anti-B, when they do not carry the B antigen themselves, they see it in the environment, and they make the antibody (it should be obvious that group A and O people would do that, while group B and AB would not).

Sometimes, blood bankers refer to these antibodies as “naturally occurring.” I personally find this phrase misleading, because it implies that the antibodies “just happen automatically.” Come on! That’s not how the immune system works! As outlined above, it’s really just making an antibody against an antigen you don’t have!

If you think about the above, a pattern starts to emerge: People make antibodies against the A or B antigens they do NOT carry on their own RBCs. This was the relationship that Dr. Karl Landsteiner outlined way back around the year 1900, and some still call it “Landsteiner’s Law.”

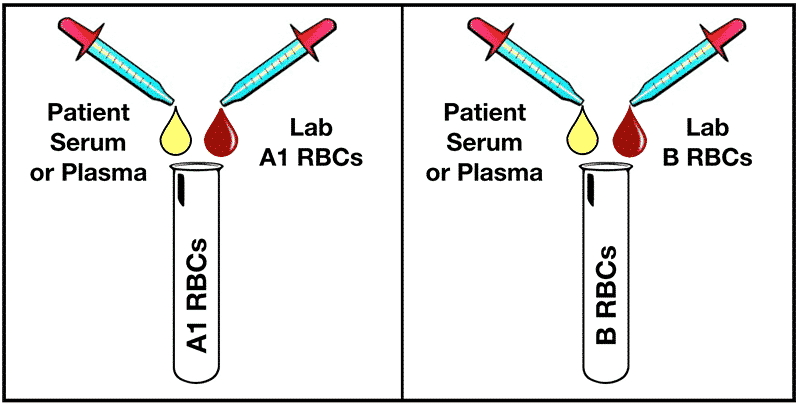

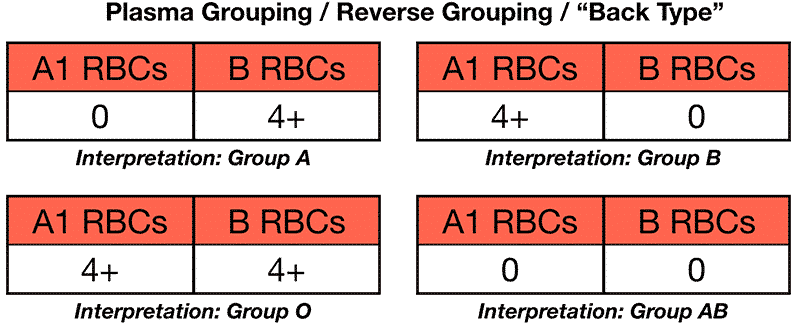

OK, so how do we test for these isohemagglutinins we expect to be there? The “reverse grouping” (also called “plasma grouping,” “serum grouping,” or the ever-popular “back-type”) is the second half of ABO testing. In the reverse grouping, the serum or plasma that was separated from the person’s red cells back at the beginning is mixed with two different red cells from the laboratory (one of them is blood group A1, and the other is blood group B). See the image below for how this looks.

So, let’s swing this back around to how the reverse reactions actually appear. Here are the four “normal” possibilities, along with the interpretations:

Tips and Tricks for Serum Grouping Interpretation:

- Get used to “reversing” things in your brain! What this means is, if you see reverse grouping results that show only reaction with laboratory A1 red cells, your brain should quickly say, “ok, this person has only anti-A, so he must carry the B antigen on his red cells; therefore, he is group B.” Likewise, you should do the same with reactions only with laboratory B cells (Interpretation: Group A), reactions with both A1 and B cells (Interpretation: Group O), and reactions with neither (Interpretation: Group AB).

- These reactions are usually very strong, too! When we are testing adults, their ABO antibodies are usually quite well-developed and strong, so the reactions in the reverse (serum) grouping are generally 3+ or 4+ in strength.

- Antibody problems are more common than antigen problems. This means that you are more likely to have an issue with a weak, missing, or even extra reaction on the reverse grouping than on the forward grouping.

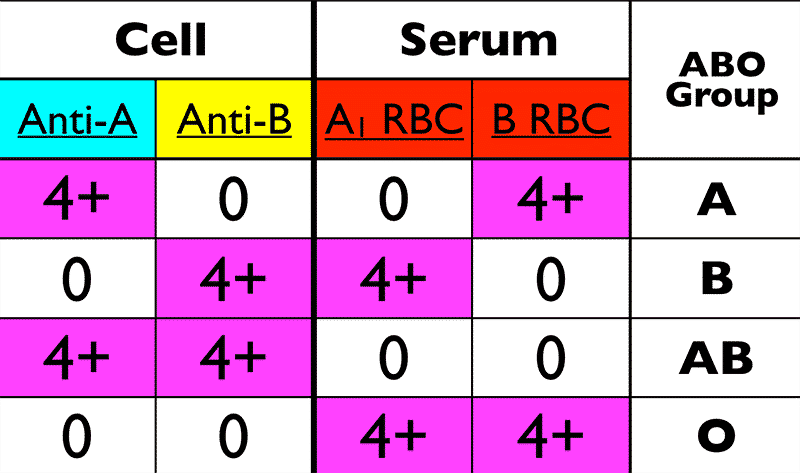

Putting it All Together:

So now you know that ABO testing has two parts, and the interpretation is based on an evaluation of the antigens present on the red cells (the forward or cell grouping, or front-type) as well as an evaluation of which ABO antibodies the person being tested has in their serum/plasma (reverse or serum/plasma grouping, or back-type). The image below shows you where we are with our understanding.

Blood bankers can recognize ABO discrepancies (when the interpretation of the forward grouping does not equal that of the reverse grouping) in a heartbeat. That’s because there’s a little trick to it. Don’t worry, I’ll share it with you right now: “Opposites attract!” If you look at the image below, you will see that the forward group reactions are always the opposite of the reverse group. Don’t believe me? Look at group A: The forward reactions are (in order) positive – negative. The reverse group reactions are (again, in order) negative – positive. The same rule holds true for every blood group (for example, the reaction for group O: negative – negative then positive – positive). That means if the reactions are NOT opposite in pattern, you will recognize a problem right away, too.

Ready to Rock?

With this background, the basic rules of ABO testing should be fairly clear to you. You should know how to interpret a basic ABO testing panel, and you are now ready to take on the cases in Dr. Draper’s interview. Don’t wait! Go right now to BBGuy.org/054 and learn what happens when the above rules are violated! Thanks for reading!